Survival of the fittest

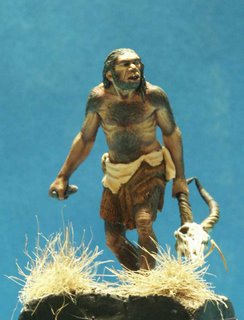

Picture: a contmporary view of our Neanderthal cousins

A recent study has shed new light on the displacement of our hominid cousins, the Neanderthals, by our human forebears. The emerging picture reflects themes that are highly illustrative of selective pressures at work even in our modern day mass societies.

The archeological research from the University of Connecticut and other universities reported that some 30.0000 to 40.000 years ago “each population (i.e. Neanderthals and modern humans) was equally and independently capable of acquiring and exploiting critical information pertaining to animal availability and behavior.” They furthermore suggest “that developments in the social realm of modern human life, allowing routine use of distant resources and more extensive division of labor, may be better indicators of why Neanderthals disappeared than hunting practices.”

Doesn’t this ring a familiar bell? Differences between contemporary human populations are all about the ability to organize and communicate at great distances. In particular, the white western variation of humanity excels in this capability. And our variation does so at the greatest possible expense of the remaining populations of homo sapiens. Don’t we?

For our capability of networking and global organization, our power of communication between and within unparalleled conglomerates of human co-operation exceed anything that life on our planet has seen before, and that – at the same time – has been such a threat to it. This is not only the case in respect of the many variations of life that we have deliberately or thoughtlessly whizzed away into oblivion; it also holds true for the lives of a great many of our brothers and sisters - modern humans - of other cultures.

Yet we choose to arm ourselves against them in a highly primitive way. Does our way of life hold so little attraction to others that we can only say: if you don’t like us, we will fight you? The Neanderthal example should give us the conviction that a better quality – and organization – of life should in the end prevail against any lesser alternative, and that there is no need to fight for it – only to demonstrate it.

Sure enough, people will say: but what if other humans decide to fight and throw airplanes filled with kerosene into our skyscrapers? I agree, it is the saddest possible tragedy, and anyone is justified to enhance defenses against it.

But the main thrust of our energies should not go into defense, let alone outright war. If we wish to survive ultimately, our best prospects are gained through the quality – and sustainability – of the way of life we choose for ourselves. Our best offense is in increasing that quality, and allowing our immense capabilities of communication and organization to truly work in our advantage, and – ultimately – in the advantage of people who today we might label as ‘adversaries’.

The greatest tragedy (well, at least for you and me) would be if the Neanderthals in the end – are us.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home